God & the Great Pumpkin

Earlier in the week, I decided to move a fallen tree on my own and it decided to fight back. The result has been a pulled muscle in my lower back and a few days of lying around. Last night my daughter joined in my get-feeling-better-movie-marathon and we watched “It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown,” a classic from my childhood, though made over a decade before my birth.

Like a light piercing through a foggy night, a scene stuck out to me for illustrating the secular v. sacred debate. It was likely just a small moment of clarity amidst my muscle-relaxer, and prescription-strength Ibuprofen, induced hibernation. Call it what you will. Here it is.

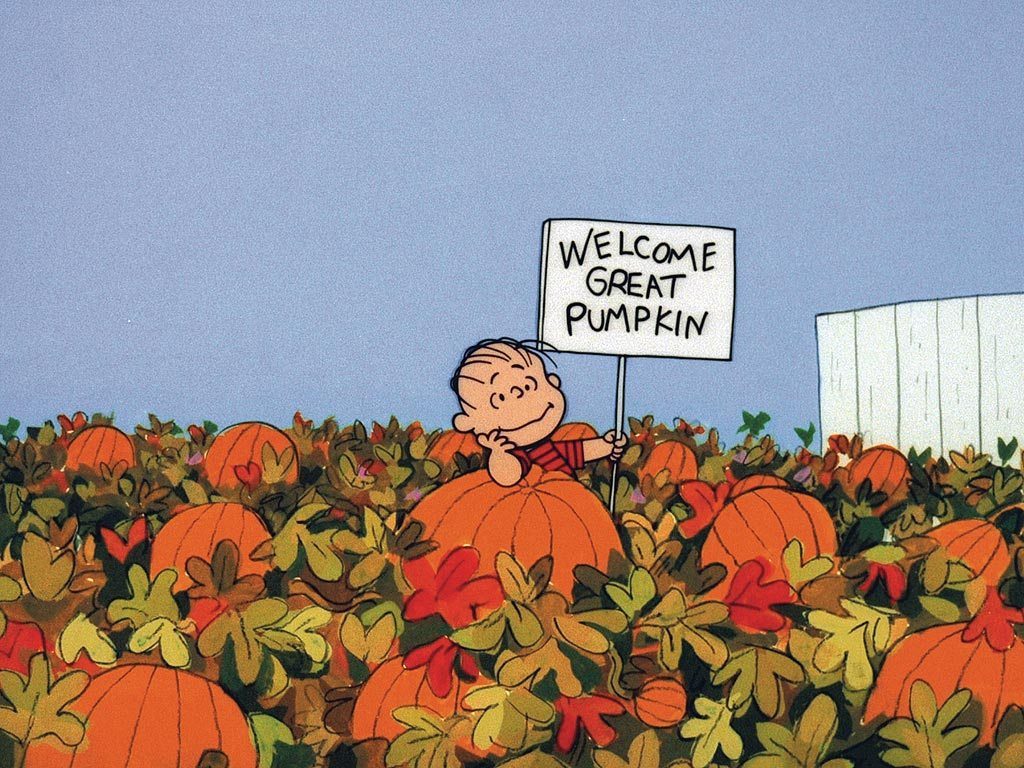

The blanket obsessed boy named Linus is confident of the existence of a powerful being whom he calls “the Great Pumpkin.” So much so, he is willing to give up the temporary pleasures of acceptance, merriment, and sweets offered by a night out with his friends. After all, the Great Pumpkin will fly through the sky and deliver gifts to all the boys and girls. Who needs their costumes and candies?!

Linus describes it thusly, “Each year, the Great Pumpkin rises out of the pumpkin patch that he thinks is the most sincere. He’s gotta pick this one. He’s got to. I don’t see how a pumpkin patch can be more sincere than this one. You can look around and there’s not a sign of hypocrisy. Nothing but sincerity as far as the eye can see.”

Like every other year, the Great Pumpkin doesn’t show up, and Linus is left candyless, cold, and alone in the pumpkin patch. At the end of the feature, Charlie Brown and Linus share a moment of reflection in which Charlie offers a word of encouragement of how he has done stupid stuff before too. Linus gives an insolent response, doubling down on his belief in the Great Pumpkin.

This whole scene can look a lot like religious people and their faith in God I would suppose, particularly to someone on the outside, viewing it all through secular eyes. After all, Linus could have received gifts by hitting the pavement and pounding doors with his friends. He could get it all without some mystical pumpkin who never shows up. Instead, he’s happy to isolate himself, cling to belief, and make excuses for the all-powerful Great Pumpkin.

Here’s where the comparison breaks down. We have to compare caramel-apples with caramel-apples, you know what I’m sayin’?

First, the Christian story is not about an alternative between two choices both of a natural explanation. With Linus, it’s either gifts from people or from a flying pumpkin, neither presented as having some supernatural origin. The Christian view is that there are two worlds, two realities, a physical one and a non-physical one, a natural one, and a super-natural one. Sure Linus could get something quite similar in life without belief in a great pumpkin. In fact, his faith holds him back. But this is very unlike the Christian view of reality.

Second, Linus believes in the Great Pumpkin without any shred of evidence. The humor in the story is the blatant similarity between the Great Pumpkin and Santa Clause. But at least for Santa Clause there is some historical relevance regarding a third-century religious leader known for practicing generosity named Saint Nicholas. Conversely, Christianity is entirely based on a singular claim of a historical event (ie. the resurrection of Jesus) for which there are layers of arguments and relevant historical data.

Finally, the Great Pumpkin doesn’t really pass the Pascal test. Pascal, the seventeenth-century philosopher, argued that if a person is wrong about their belief in God, in death they will never know. Similarly, if a person doesn’t believe in God, and they’re right, in death they will never know either. However, if a person is wrong about their unbelief in God, if God does in fact exist, then in death they will be well aware of their error. The best bet then, according to Pascal, is to live one’s life in a God-oriented kind of way.

For Linus, whether or not the Great Pumpkin exists is a reality only affecting this life — really only something with relevance one day a year — at the end of the month of October. Christianity, on the other hand, entails a life to come, but in such a way that it imbues this life with a framework of purpose, a fountain of meaning, and foundation for virtue. But can’t you find those things apart from belief in God, like Linus could have gotten some treats without belief in a Great Pumpkin? Yes and no. Like so many others have argued elsewhere (read Tom Holland’s Dominion or Glen Scrivener’s Air We Breathe), I would say that secular values really only make sense when seen through religious lenses.

More importantly, if there is another world to come, if there really is something beyond the grave, then belief in God matters far more than just finding purpose in the here and now. The Christian story goes even further claiming that God once came down to tell us this himself. And as Linus once taught us in another animated feature, this is the very meaning of Christmas.