A Gorilla, a Lizard, and Our Longing for Cosmic Justice

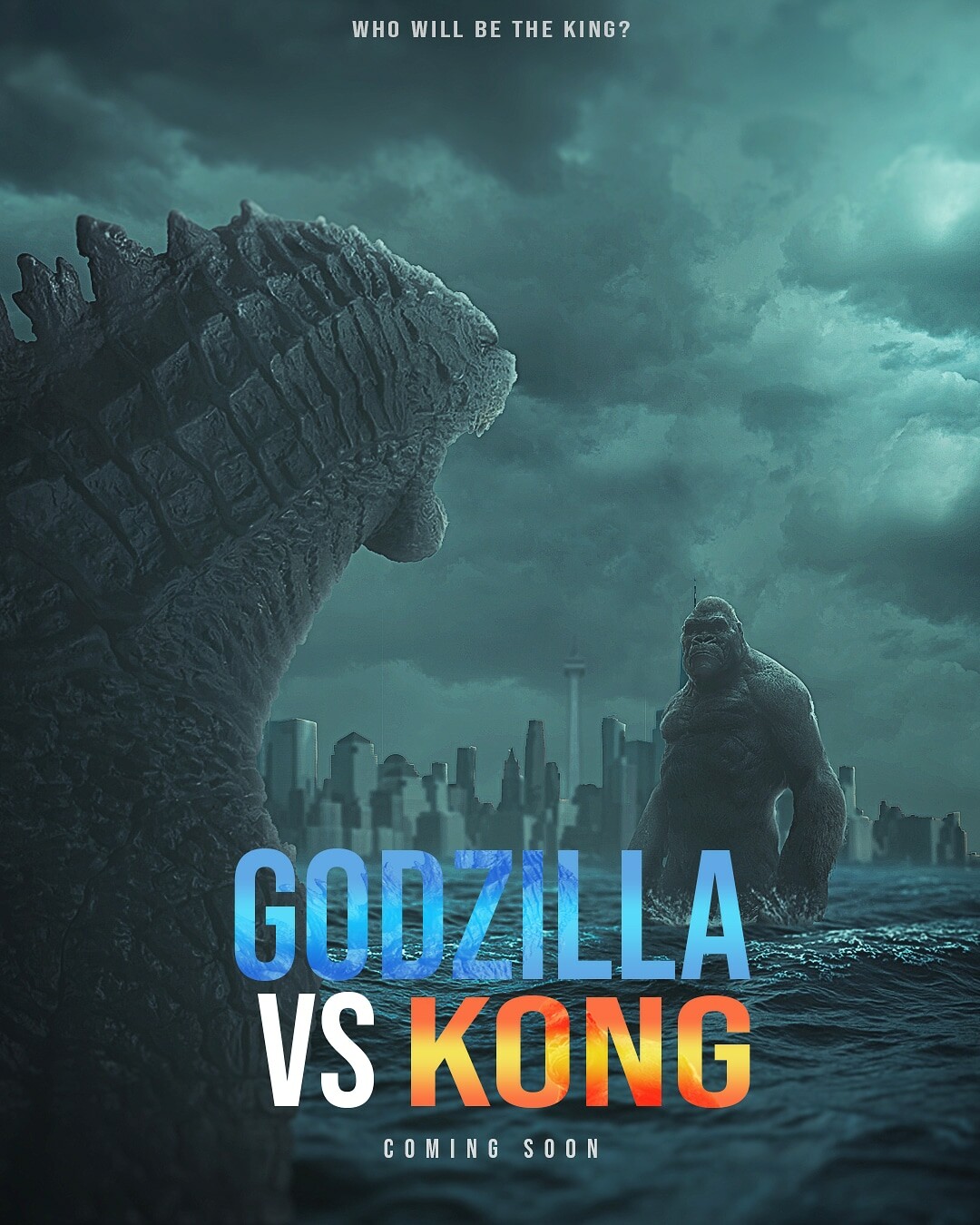

Last weekend I experienced the joyful cognitive dissonance of returning to a movie theater. It’s one of the simple pleasures I miss from our days before the global pandemic. I brought my twin sons to see the King Kong vs. Godzilla pic. It was what we expected: minimal plot, maximum effects, and epic battles.

It’s the biggest box office hit since theaters began reopening. I think that’s likely for several reasons, some of which have more to do with popcorn than philosophy. But I do think movies like this give us a common enemy, a cosmic hero, and, what Tolkien called, a eucatastrophe. In a world where we have little control, we are drawn to those stories where in the midst of darkness, hope emerges and goodness triumphs.

Forgive the reference to my own writing, but I was reminded of this passage from a book I published a few years back called Christ or Chaos:

But might the optimistic impulse, like the religious one, actually point somewhere? Like the religious outlook, if our optimism is a false view of reality imposed on us by evolution, then how can we break free from the illusion? Should we embrace despair? Must we consider human optimism irrational? Given atheism, I don’t see how it can be anything but irrational. Consider Bertrand Russell’s summary of his atheistic perspective in his essay “A Free Man’s Worship,†included in his book Why I Am Not a Christian:

That man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labors of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

According to Russell, humanity is the result of blind causes and purposeless effects destined for extinction. This is where we, according to Russell, must begin if we hope to build a safe habitation for our souls, whatever that might mean.

In his artistic conclusion, it seems he was attempting to open a door to a possible escape. But those who follow his lead will find one set of spiraling stairs after another, leading eventually to a final door that is locked, is double-bolted, and bears a handwritten note that reads, “Better luck next time.â€

There is a stubborn human habit of living as though we are a part of a better story, something grander, something truly worthy of our lives. It’s as though—dark as things look, with rumblings of war, natural disasters, political unrest, economic recession, disease and death—we are holding out hope that someone, somewhere might save the day. We’re waiting for superman.

Seriously. Almost all the big-name superheroes grew out of a time of unrest and uncertainty. A CNN article titled “Superheroes Rise in Tough Times†chronicles this phenomenon. Batman, Superman, and Captain America all emerged in the midst of the Great Depression and the early years of World War II. Our yearning for supernatural intervention can be seen in other historical developments as well.

During the Civil War one citizen wrote to Salmon Chase, US Treasury Secretary, asking that the “goddess liberty†be replaced on our currency with a statement of our nation’s reliance upon God. Shortly thereafter, the expression “In God We Trust†was imprinted on our coins. This creed was not added to paper currency until the 1960s, when America was again under extreme duress due to its prolonged military engagement in Vietnam.

Similarly, the phrase “one nation under God†was not added to the Pledge of Allegiance until the mid-1950s, which historians link to a growing national concern over the threat of communism, known as the Red Scare. In times of economic recession, war, and national horror we express our need for divine mediation. In our most vulnerable moments we let the secret out: we really do know of something greater than nature. But this awareness cannot survive in a spiritual vacuum. It is part of the Christian way of viewing the cosmos. It is part and parcel of the Christian narrative.