Our Orphan Hearts (A Reflection on John 14)

The fourteenth chapter of John’s gospel reads like a Q&A time at a Christian conference. John records Jesus responding to perennial questions offered by three seemingly insignificant disciples. Thomas, Philip, and Judas (not Iscariot), all make cameos in the chapter.

Each disciple has a burning question. Thomas asks “how can we know the way” (John 14:4). Philip asks “what is God like?” (John 14:8). Judas asks “how can we know God?” (John 14:22).

These questions all point to a fundamental human longing for place and person. The holidays extenuate these human longings, don’t they? We travel great distances to be near a place and near a people. Even if we can’t travel, our hearts long for them.

Pining for Place and Person

The biologist, naturalist, and author E.O. Wilson (who died a little over a year ago) credited this to evolution. Wilson believed our desire for particular places harkens back to our past in the African savannah. An article in The Atlantic describe his view:

In many of his writings, Wilson places hope in arguments that range from the ethical (humankind will ultimately awaken to its responsibility to the Earth), to the genetic (our evolutionary background has conditioned us to yearn for such things as unspoiled savannas and wilderness), and finally to a kind of naturalist’s spiritualism. “For the naturalist, every entrance into a wild environment rekindles an excitement that is childlike in spontaneity, [and] often tinged with apprehension,” he wrote in his 2002 book, The Future of Life. Every such experience, he continued, reminds us of “the way life ought to be lived, all the time.”

American history illustrates our hope for a person. In times of political unrest, this spiritual optimism is on full display. As a result of the national turmoil of the civil war, we added “In God We Trust” to our coins. We added it to our paper currency during the war in Vietnam. During the “Red Scare,” the national concern about communism, we added “one nation under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance. Our history shows our religious impulse.

Even our superheroes were all born in challenging times. Batman, Superman, and Captain America were all products of the Great Depression and World War II. In short, iff you cut us, we bleed spiritual. Under the surface, we’re holding out hope that there is more than nature.

Jesus offers us both a place and a person in John 14. “I am the Way, the Truth, and the Life,” Jesus told Thomas. To Phillip’s question about understanding God, Jesus gives what Christian theologians would call a Trinitarian answer, explaining God in terms of Father, Son, and Spirit. And to Judas’s question about knowing God, Jesus explains that to those who believe, “God will make his home with them” (John 14:23).

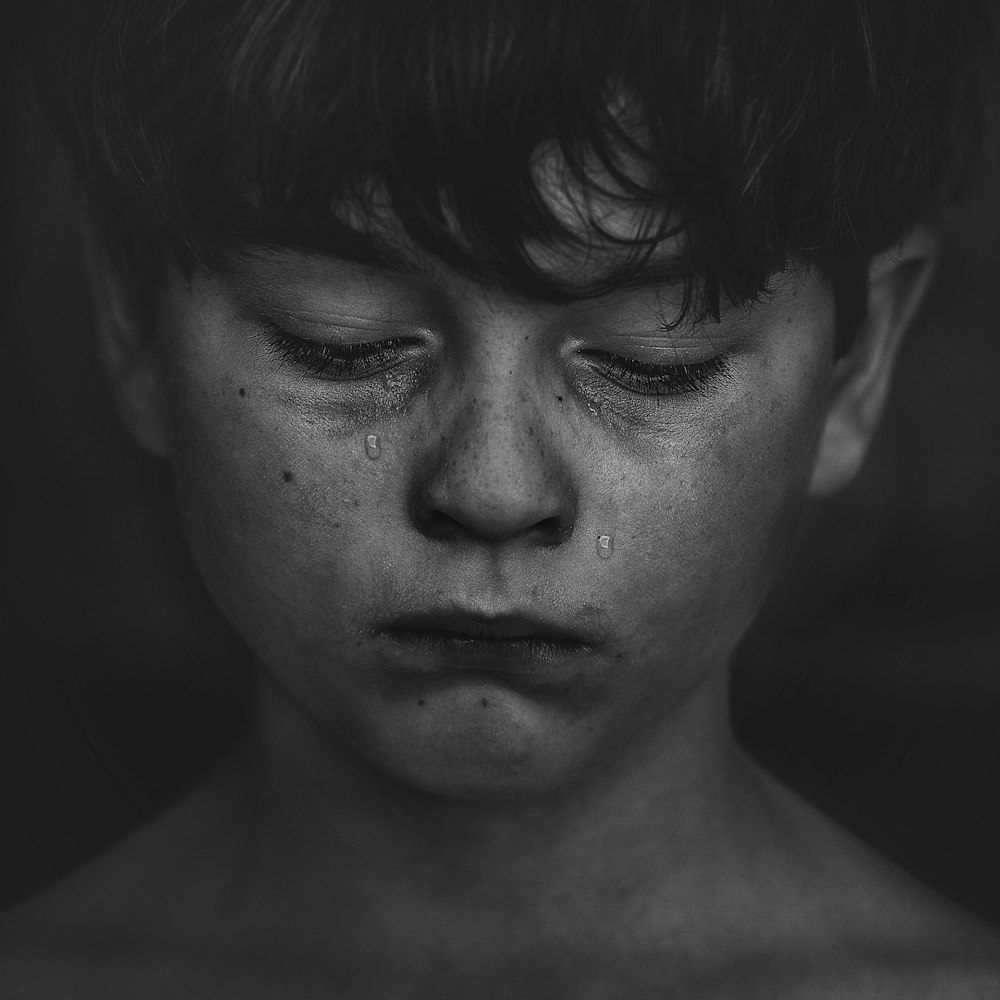

Jesus promises the disciples he will not leave them as orphans (John 14:18). An orphan is a person without a permanent place or person. It’s hard to think of more evocative language to describe our spiritual longings. We desperately need place and person. Jesus offers us both.

We often feel as orphans in the world. Even when we believe, we still long. We’re still lonely. But Christians find comfort in the promise that Jesus will not leave us this way. He is preparing a place for us, and he has promised to return. Our longings for place and person converge in Him.

A Narrow View

Isn’t Jesus’s claim to be the way extremely narrow? Yes. It is. But so is every ultimate claim about reality. An atheist friend once asked me if how I could live with such a narrow view as Christianity. My response to him was to ask how he could live with such a narrow view as atheism.

As a Christian, I have a similar perspective on the world as all of the monotheistic religions. Islam, Judaism, and Christianity all believe there is one God. My atheist friend considers all of them to be wrong at best, or delusional at worst. Most in the world recognize some higher reality, whether many gods or the universe itself as divine. My friend thinks they’re all wrong too. Isnt’ that narrow?

One could respond with something of a compromise, saying something like “all religions are true.” In the end, this is far more narrow than it appears. You can only make such a claim by ignoring what the orthodox in any major religion actually believes. Such a view would then restrict anyone who actually believes their religion to be true. Isn’t that narrow?

You could move to the other end of the spectrum and simply conclude that there is no such thing as truth. That sounds really broad-minded, doesn’t it? The problem is, many people in the world believe there is such a thing as truth. Again, look to the major world religions. Such a perspective would have to say they are all wrong or delusional. Isn’t that narrow?

The reality is every one holds a position that is far more narrow than they realize. So, the question isn’t which view is less narrow. It’s a matter of truth. Which view is true? You could conclude by saying you can’t ever really know what is true, but that ends up back in the same dilemma of a narrow position that restricts all of the people who believe truth is knowable. What are we to do?

Christians should lead the way in respectful conversations among those seeking truth from any background. It’s a bumpy road we all find ourselves traveling on. We are acutely aware of the universal impulse to find place and person. We feel it in our bones. Like these three disciples—Thomas, Philip, and Judas—we are all trying to find a way, to understand God, and to connect with some kind of ultimate reality.

The Christian believes this search can only take us so far though. As Paul said, we are searching and grasping for God, though He is not far from any of us (Acts 17). An orphan cannot find place or person on their own. Their status alone points to the fact that they need someone to find them. And John’s gospel says this is precisely what Jesus has done.